1. It is easy to look upon the remains of anything left devastated and to remark upon the gratuity of the violence. To say of the boy, or the church, or the block—oh there was some beautiful thing now left no longer operative. But what happens when the eyes peel themselves away from the wreckage, and those who flock around the death still go on living. This is one of the intimate questions that Willis-Abdurraqib’s book contends with, and nowhere more candidly, than in the poem, “After The Cameras Leave, In Three Parts.” In part two of the poem, “The Convenience Store’s Broken Glass Speaks,” the glass says of itself:

I part the whole

country / I Moses the Midwest / come children / walk through my toothed bed

/ to the other shore / we don’t talk about death over here / we don’t speak its

name / we don’t speak of leaving / we wake up to a new day / we don’t think

of who didn’t / look at me here / stretched out on this holy ground / like I’m

almost human / like I’m almost worth grieving / and why not? / people have

to mourn the shatter / of anything that they can / look into / and see how

alive / they still are

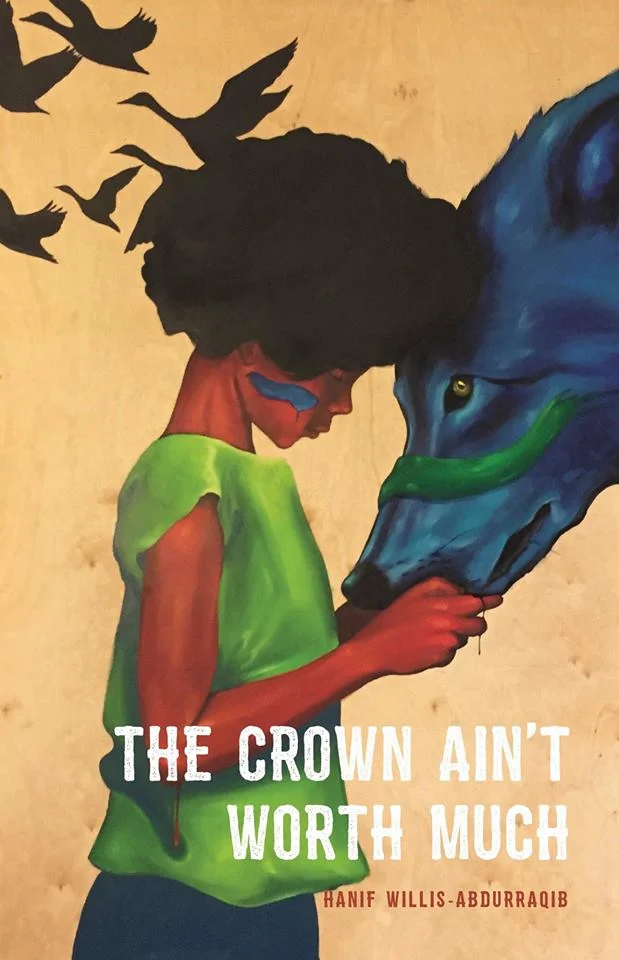

2. Reading The Crown Ain’t Worth Much, I spend time considering the contour of a moment— the ways in which language can, and does at times, ruin me. Individual moments explode into their context and meaning, and become mirror houses of signification. I read Willis-Abdurraqib’s wordsmithery and see mouths: mouths opening in hunger, mouths surrendering to mirth, mouths moved to sorrow and to praise; also, the mouths of rivers, of valleys, of streams pouring lush and open into expectant lakes. There is great power in the interpretation of moments, in the telling and retelling of one’s story & in The Crown Ain’t Worth Much, I’m reminded of the power of language, of the ability of words to substantiate, to call forth that which is needed.

3. Willis-Abdurraqib creates imagined narratives that piece together ancestral memory and center the importance of lineage, how this being, the author, came to be. Often times, the interpretation of the moments happen in media res, at the time of the events, rather than in their aftermath. In a very real sense, the moments in The Crown Ain’t Worth Much speak for themselves. In the poem “My Wife Says That If You Live Twenty Years,” when a women on the elevator ask the speaker and his wife how many children they will have, in deference to his dead, the speaker’s reflection replies, “enough to carry endless caskets through the/sinking mud.” In the poem “The Ghost of the Author’s Mother Has a Conversation with His Fiancée about Highways,” the ghost of the author’s mother apologizes to his fiancée for his inability to wear suits, explaining to the Author’s fiancée:

My boys don’t bother with seasons anymore. My sons went to sleep in the spring

once and woke up to a motherless summer. All they know now is that it always

be colder than it should be. I wish I could fix this for you.”

Three of the poems in the collection are written in the voice of the ghost of the author’s mother. Another four are written in the voice of the author’s barber. The poems from the barbershop focus specifically on the violence of gentrification, and the ways in which these social patterns physically affect space and the people that inhabit it. The poems are titled “Dispatches from the Black Barbershop, Tony’s Chair [Insert Year].” They detail the events going on in Columbus at the time, but also recount the changes that have occurred since the speaker has last visited the barbershop, as he moves further and further out from the city, into the college town of “Bexley,” and then ultimately into the suburbs. In the last of these, “Dispatches from the Black Barbershop, Tony’s Chair 2015” we get a very real sense of how the ongoing changes throughout the book are affecting Tony:

nigga you might be my last cut they done took all ‘cept this chair and these

blades same ones I been using since ’89 they still sound the same they still cut

clean but they loud they sound like a bulldozer comin these blades been watchin

all that black hair fall since we got here these blades been watchin all those

black buildings fall since we got here niggas ain’t got nowhere to go except under

the ground my son got locked up fuckin with those packs trynna make money

for the family we ain’t been eatin ever since they built that salon for the white

folks next door we ain’t been eatin ever since the white families moved in and

couldn’t pronounce my son’s name niggas hungry everything for sale out here

4. So many of the poems in The Crown Ain’t Worth Much are marked by isolationism, linked to, and intimately connected with, states of heightened emotional sensitivity. The quote, “Loneliness comes with life,” (Whitney Houston) is the epigraph that begins the third section of The Crown Ain’t Worth Much. The speaking voice of the poems is alone, but that loneliness comes from the consideration of their own mortality and the mortality of those around them. In the face of the uncertainty of life, and the uncertainty of when their death might become them, the speaking voice makes the radical decision to live, and to love, in spite of, and even, in the face of death. In the poem, “On Melting,” Willis-Abdurraqib writes,

everywhere we look is another anchored ghost clawing at the

window but this is the season where I will make the face

of a girl on a cookie and pass it to her across a room full of

strangers which is a weird way to say

I think I could love you until even the sun grows tired

of coming back every

spring to forgive us for another season of hiding

What we see expressed here is the voice of a speaker wanting and willing themselves to love. All throughout The Crown Ain’t Worth Much there is an earnest desire to engage in acts of empathy; to see one’s self in the rising sun and in the face of a lover, and even in the face of the dog searching for the perfect place to release its morning sacrament.

a gift to show that you can still

hold things

That you are not yet

ready for burial.

The intentional empathy of the speaking voice is harshly juxtaposed against the violence of a world, which willfully looks away, refuses to see itself, in anything, except that which they can “look into / and see how alive / they still are”

5. And maybe this is why the speaker of the poems is always running. In The Crown Ain’t Worth Much phrases such as “and then,” “I mean,” “right,” “you know,” “maybe,” function as exodus, mimicking the movement of time and also qualifying the tightrope dance between lines in the poems. The word anaphora comes from the Greek phrase “carrying up or back.” It is the repetition of a word or phrase at the beginning of every clause. The Crown Ain’t Worth Much is saturated with anaphora— clauses press up against one another relentlessly. The phrases become vehicles that carry us. The words “and then” delineate between what was and what now is, & ultimately what will become. Time folds in on itself; the speaker becomes synecdoche, the poem poured into one singular vessel. The poems in The Crown Ain’t Worth Much are heart rendering. They recreate these moments that the world has supposedly spoken on. And yet, the poems exist in the aftermath of violence; in a world that trivializes the pain we have experienced, the poems offer us new names. The language of the penultimate poem is generative,

“I say Mike and a cardinal lands on my shoulder

I say Trayvon and a rainbow stretches over a city where it doesn’t rain

I say Sandra and a new tree grows in my father’s front yard

It stretches to the sky. It carries armfuls of light back to where he rest

And reminds him I am still whole

I am still whole

I am still whole

In another summer of black smoke

Willis-Abdurraqib takes the very real materials of his life, what the world has given and provided him, and imagines himself a world in which he can be beautiful, whole. In a summer laden with sacrifice and the subterfuge of all that wishes us smoke, Willis-Abdurraqib writes an ode to living, to the making of and the rediscovering of the self, and of home.