1. As readers, it is easy to become wary of a poetics founded upon something like wonder. These are abstractions older than language, and in the hands of a lesser writer, they could become little beyond tired tropes. In Portrait of the Alcoholic, Akbar renders delight and surprise into new forms that have not yet failed to leave me breathless. One of the earlier poems of the book, ‘Do You Speak Persian?’ addresses the speaker’s loss of his first language:

Some days we can see Venus in mid-afternoon. Then at night, stars

separated by billions of miles, light travelling years

to die in the back of an eye.

Is there a vocabulary for this – one to make dailiness amplify

and not diminish wonder?

The question Akbar poses here is perhaps unknowable but the poems that make up Portrait of the Alcoholic come as close as anything can to providing an answer.

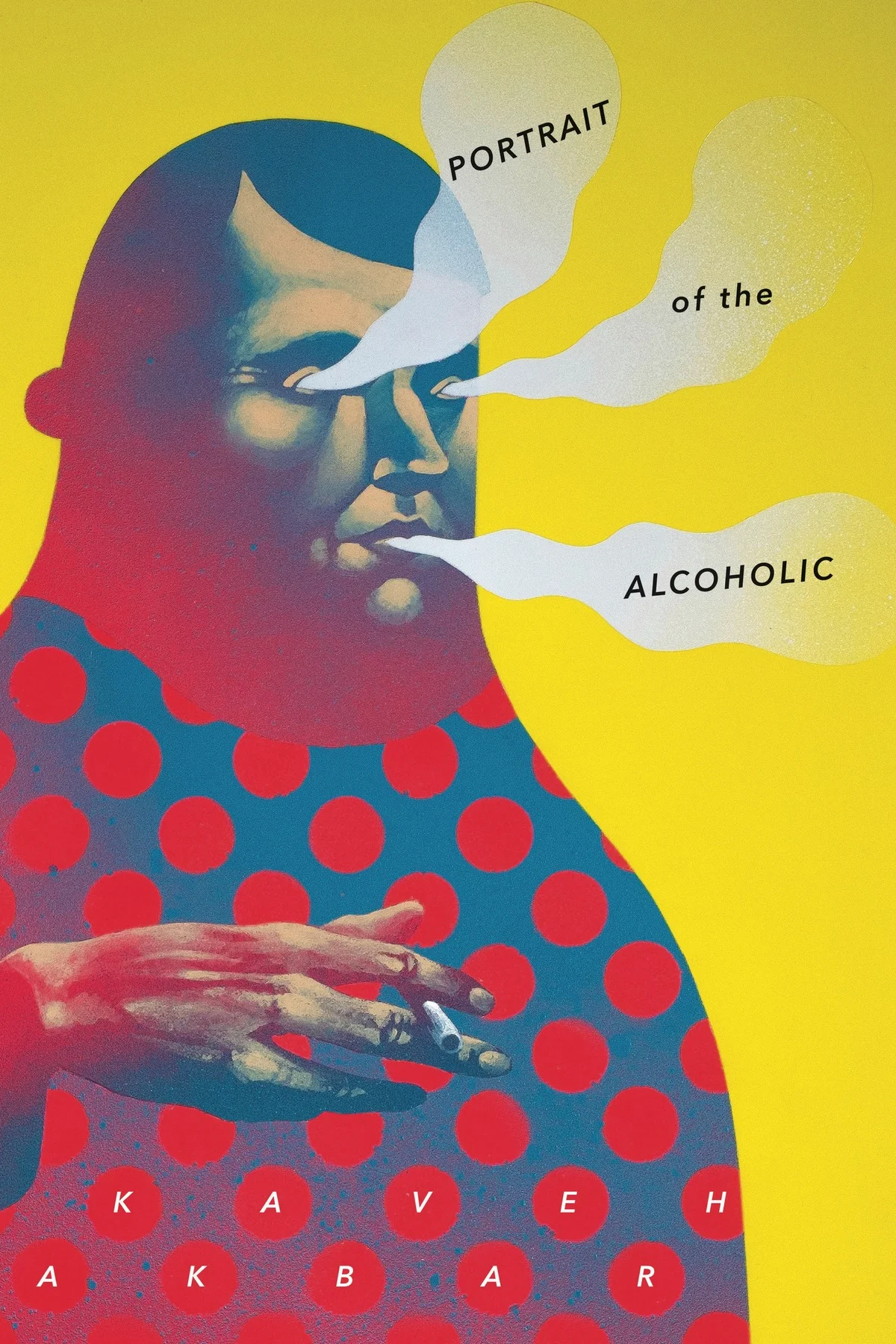

2. Portrait of the Alcoholic is dedicated to drunks. The dedication of the chapbook to this specific audience resonates with the honesty of the central and titular struggle with addiction. On a structural level, the collection seems to be organized around the progression through the Alcoholics Anonymous’ 12 step program. Following the title series from beginning to end, we see this character, the drunk, being renamed “the alcoholic” (step one involves acknowledgment of the addiction) and coming head-to-head with withdrawal, craving, and ultimately a reflective sort of solitude. There’s grapplings with an understanding of God that intertwine with the loss that stems in part from separation from the speaker’s home country of Iran. Religion, making amends, even the taking of personal inventory – all of these are central aspect to the twelve step program. Yet even without an intimate knowledge of the world of addiction or the rhetorical world of Alcoholics Anonymous, a reader can still make sense of what Portrait of the Alcoholic is saying; it is Kaveh’s singular gift, to write a bookful of poems and have all of them be at once lyrical and gorgeous, yet still deeply fathomable.

Throughout that title series of poems, alcoholism and addiction are personified into the poetic addressee of “you.” This sort of apostrophe is less interested in animating what might otherwise be voiceless and more focused on giving the poems a kinetic direction, propelling them. “This can guide us forward / or not guide us at all” Akbar writes in the poem ‘Portrait of the Alcoholic Three Weeks Sober,’ and perhaps this too is meant as a means of understanding the chapbook’s architecture. These poems progress through time and space meaningfully, and guide us not quite forward, but ahead.

3. Portrait of the Alcoholic succeeds on both the macroscopic and microscopic level. One of my favorite poems in the book, ‘Unburnable the Cold is Flooding Our Lives,’ shows the speaker again navigating the rivers of wonderment, while being destabilized with their own irreverence and skepticism. The procession of thought in the first two couplets exemplify this:

the prophets are alive but unrecognizable to us

as calligraphy to a mouse for a time they dragged

long oar strokes across the sky now they sit

in graveyards drinking coffee forking soapy cottage cheese

into their mouths my hungry is different than their hungry

The unpunctuated breaks in many of Portrait of the Alcoholic’s poems hand over the reigns of poetic energy to the white space of the page, and ‘Unburnable the Cold...’ manages to harness that in full effect. As readers we leap from idea to idea, unbracketed, and leave with the feeling that we’ve just jumped over a series of sudden fissures in the ground. It’s so exciting, so utterly exhilarating, to witness a mind that can take those sudden turns, from death to tomatoless salads. The poems in Portrait of the Alcoholic are charged with life, bringing a slow smile to my face when read aloud, (as with any time I can make the mouth-motions for “soapy cottage cheese”). The near rhyme of “oar strokes” and “forking soap” in “Unburnable the Cold…” is so simple, yet a moment that makes me inexplicably gleeful. These lines offers glaring contrast to one that occurs soon thereafter: “after thirty years in America my father now dreams in English.” This poem in particular follows a pattern of lyrical delight undercut by the plainspoken, ending with a chant-like repetition of the phrase “and yet,” leaving the reader helplessly cartwheeling around in the crater.

4. Portrait of the Alcoholic is interested in the spaces between things, in the “gulf between / what I’ve been given / and what I’ve received.” (‘Portrait of the Alcoholic Stranded on a Desert Island’) One such gulf is language, but the other primary space that Akbar explores here is the many-gulfed presence of God. In ‘Learning to Pray,’ the speaker watches his father “kneeling on a janamaz // then pressing his forehead to a circle of Karbala clay” and thinks not of the rituals of devotion, but instead “only that I wanted / to be like him.” Yet this too, is a sort of devotion, and Akbar knows this; God takes on many forms throughout the collection. What is most interesting about the role of faith in Portrait of the Alcoholic is not the freeness with which the divine can be questioned, but the much more human notion of interrogating what it means for there to be a divine presence at all. In ‘Personal Inventory: Fearless (Temporis Fila)’, the speaker notes that “I try not to think of God as a debt to luck / but for years I consumed nothing / that did not harm me / and still I lived...” Faith is not the end goal of these poems; any poet who refers to God as “our father who art in heaven – always / just stepped out” is up to something beyond mere devotion. The speaker’s relationship to God is one that allows the reader a glimpse into a deep place of interiority, the last refuge of the self. And in Portrait of the Alcoholic, no aspect of the self is able to go unseen.

5. In general, we have come to expect the endings of books (and movies, and television, etc.) to reach some sort of denouement, something like a concluding moment. Portrait of the Alcoholic resists that closure. In the collection’s final poems, Akbar does not resort to wish fulfillment, or moving on, or any sort of divine clemency. As we know from the title alone, these poems are a portrait of an alcoholic, and portraiture is meant to achieve some sort of truthful representation of a person. The ending we are given is the nearest sort of truthful conclusion that any still-living alcoholic can offer: addiction does not end. We carry it with us, quiet or blaring, for the rest of our lives. Or, as the poet says it:

I hold my breath.

The boat I am building

will never be done.

- ‘Portrait of the Alcoholic Stranded on a Desert Island’