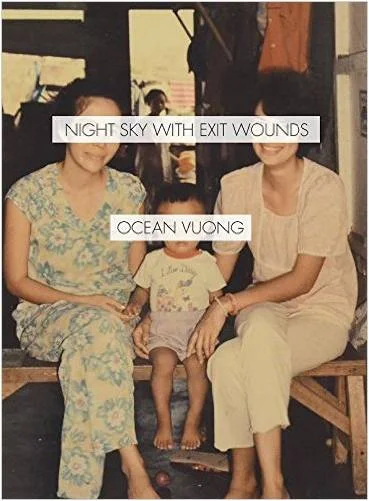

Five Reasons to Read: Night Sky With Exit Wounds,

by Ocean Vuong

// review by Sarah Maria Medina //

Ocean Vuong, author of two poetry chapbooks, Burnings (Sibling Rivalry Press 2010) and No (Yes Yes Books 2013), debuts his first full collection Night Sky with Exit Wounds (Copper Canyon Press). Vuong, who enamored many readers with "Someday I’ll Love Ocean Vuong" (published in the New Yorker) is quickly becoming North America’s most beloved poet. Listen to his readings at a poetry soiree or online and the magical quality of his gentle voice cradles his words to your earbuds until you are left seeking out more.

In Night Sky with Exit Wounds, Vuong returns us to his birth country, Viet Nam, and breaks apart our linear concept of time, bringing the war and its recipients back to our living room. The rice fields in Saigon burn once again. Here, war isn’t something that ends when the soldiers return to their homeland — war continues through formed pathways that come about from its violence.

When your childhood is shaped by war, there is a need to peel back what is called the past and look for answers, because the American war in Viet Nam didn’t stop on April 30th in 1975 — because it expands and breathes like some terrible creature that resettles and nests in new lands. Think Iraq. Think Afghanistan. Think Oklahoma. Think Borderlands. Think Baton Rouge, and a woman in a long dress standing calm in front of the militia. Vuong brings a new layer to the war narrative — he brings sensuality, and life, and bullet wounds with light — you peer through them to the other side.

1. In an NPR radio interview, the host, Michel Martin, asks Vuong how he hopes Americans will see him, and Vuong answers that he hopes they will see him as a brother, because he is American too.

In this country that pulls apart the definition of American, that forgets that America extends all the way South, that American is immigrant, is migration, is movement, is not stagnant or built borders or white patrol, that America is Black, is brown as the Native tribes here first — Night Sky with Exit Wounds reminds us that America is Ocean Vuong, is poet, is brother, is queer, is love, is field of burning, is field composting to bloom. In "Ode to Masturbation" Vuong unburies the narrative of truth telling, intimately extending “the smallest bones” to those unremembered, unacknowledged or unsung.

in the graves you

who ignite the april air

with all your petals’

here here here you

who twist

through barbed

-wired light

despite knowing

how color beckons

decapitation

i reach down

looking for you

in american dirt

2. Fatherless as a sense of absence, as a wound, as only as long as you remember, shines a narrative thread that weaves through Night Sky with Exit Wounds. In "Telemachus," Vuong “like any good son” pulls his father from the water.

I might sink. Do you know who I am,

Ba? But the answer never comes. The answer

is the bullet hole in his back, brimming

with seawater. He is so still I think

At the end of the "Telemachus," Vuong examines his father and finds “the cathedral in his sea-black eyes.” There is something holy being constructed within this poetic recalling of father: a cathedral once bombed becomes a sea of trees or his father’s eyes. In "Deto(nation)," we find father inside lungs. We find father urging flight toward the narrator’s shadow, the shadow of a boy mimicking father.

& stay. Don’t stay here, he said, my boy

broken by the names of flowers. Don’t cry.

3. Vuong has carefully sculpted each poem, given it time and place to breathe into its own form. In "Trojan," a beautiful innovative form uses white space to create definition across the page as Vuong speaks to sexuality and the horse within the human face of a boy in a dress.

between his ribs. How easily a boy in a dress

the red shut eyes

vanishes

beneath the sound of his own

galloping. How a horse will run until it breaks

into weather— into wind. How like

the wind, they will see him. They will see him

clearest

when the city burns.

As in the philosophy of the eternal return that Nietzsche popularized, time folds in Vuong’s narrative. In 1975, in Southern Viet Nam, Irving Berlin’s "White Christmas" is played as code for evacuation during the fall of Saigon. In "Aubade with Burning City," Vuong mixes Berlin’s lyrics with an intimate scene, not seen from the frontlines of war. Time is bent and shaped through white space, song falling.

Milkflower petals in the street

Like pieces of a girl’s dress

May your days be merry and bright…

He fills a teacup with champagne, brings it to her lips.

Open, he says.

She opens.

Outside, a soldier spits out

His cigarette as footsteps fill the square like stones

fallen from the sky. May

all your Christmas be white

As the traffic guard unstraps his holster.

4. As Vuong’s stanzas bend time, love wildfires through the book — love of mother and grandmother, love of missing father, love oh passionate love of men. Vuong is bold and unfearful of this love; it manifests as a blooming peony of men, flowering sacrosanct throughout the book. In "Devotion," the narrator asks to feel fully, to feel what the cold of winter snow feels like against naked flesh. Vuong extends his love for his man, the two, devotees inside the temple of lover.

Because the difference

between prayer & mercy

is how you move

the tongue. I press mine

to the naval’s familiar

whorl, molasses threads

descending toward

devotion. & there’s nothing

more holy than holding

a man’s heartbeat between

your teeth, sharpened

with too much

air. This mouth the last

entry into January, silenced

5. Night Sky with Exit Wounds speaks to mothers as survivors and mothers as companions beyond the unsurvivable. Vuong invokes the stories his family carried with them when they immigrated to the East Coast, along with their generational narratives: "a nun, on fire," running "silently toward her god," an embassy with hyacinths and a burning city. The feminine then in this narrative is memory, is survival, is perseverance, is light shining through the wound.

In "Threshold," the narrator speaks to a simultaneous weakness and strength. Each couplet is delicate, intentional, detailed with setting and sewn with emotion, and laced with a magical realism.

In the body, where everything has a price,

I was a beggar. On my knees,

I watched, through the keyhole, not

the man showering, but the rain

falling through him: guitar strings snapping

Over his globed shoulders.

He was singing, which is why

I remember it. His voice—

It filled me to the core

Like a skeleton. Even my name

Knelt down inside me, asking

to be spared.

We are reminded that the greatest accolades in life are so simple and yet so grand in their validation of our own survival. The exit wound becomes a point of departure, becomes both entry and exit point to narrative breath. Vuong finds home within the exit wound, carves out and inhabits this liminal space. In "Threshold," Vuong tells us what it’s like to go through the exit point.

behind the door. I didn’t know the cost

of entering a song—was to lose

your way back.

Then the narrator confides, they went in and lost. To enter a song completely is to lose oneself completely, to not return to the entrance point, to the nexus where the exit point is only a small bullet wound of light. And oh how different the light is once lost, and oh how different the song once sung, and oh how different the summer snow burns the body of verse.

To read more of Ocean Vuong’s work go here, here & here. To purchase Night Sky with Exit Wounds, order directly from Copper Canyon Press.