1. It’s late summer, August in New York, when LOOK arrives in my mailbox – the muggy heat that presses down on you, the groggy days and the insomniac nights. I read it in one sitting, unable to tear myself from the page. The effects are physical: dizzying, breathtaking. Later, walking down the long stretches of streets in Upper Manhattan, I find myself caught in mirages, the heat and the exhaust fumes combining to make the horizon line glimmer, a wavering overlay on the material reality of things.

This is what LOOK does to you. Sharif juxtaposes the everyday language of ordinary life, the words that are common to us, with military parlance. By doing so, she reveals the multiple layers reality has for those who have endured a military presence, who know that words shape fear and hatred as much as actions do. The effect is ferocious, implacable in the sheer violence it implies: “Lovely dinner party. Darling casualties and lean / sirloin DAMAGE of the COLLATERAL sort.”

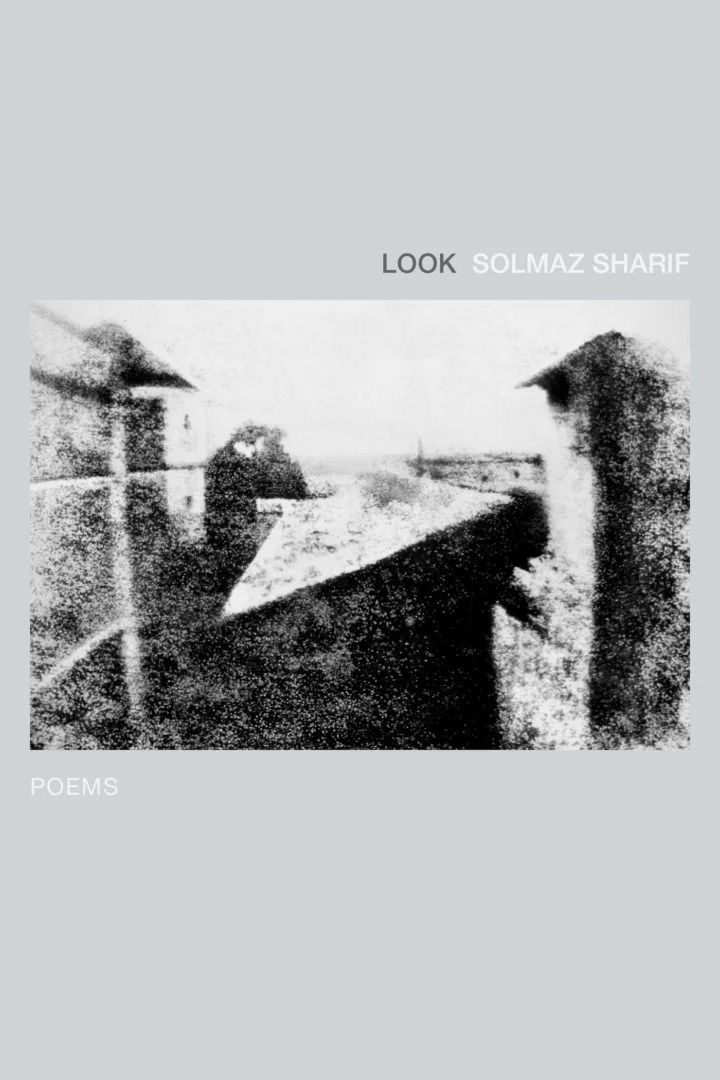

Sharif allows jargon to irrupt in language like a scab: she exposes how daily language itself has been contaminated by definitions created within a military context, so that “look” may refer to the gaze, charged with subtext; it may be used in the imperative form, the urge to see for oneself; and it can designate “a period during which a mine circuit is receptive of an influence.”

2. The small caps indicate the doublespeak & they’re everywhere, even in what we would have thought were the most benign of words: “Too LATE to remember / what I meant to write.” This hyper-presence is correlated with censorship:

in the yard, and moths

have gotten to your mother’s

, remember?

I have enclosed some −made this

batch just for you. Please eat well.

In “Reaching Guantánamo,” a series of letters addressed to “Salim” is hollowed out, with redacted parts shining by their absence.Sometimes we can guess what the missing words are, but not always, which, beyond disrupting syntax, points at the loss of meaning. War and its aftermath don’t just erase bodies; they also erase the possibility of making sense out of the world. By design, military jargon is euphemistic: it seeks to occult the flesh-and-blood consequences of its application in real life, on the ground.

PINPOINT TARGET one lit desk lamp

and a nightgown walking past the window

By inserting these capitalized words in scenes of intimacy, Sharif pulls the curtain back, tears it apart, so much so that the reader can never walk away unfazed. The implication is: we were complacent with war because the language it uses seeped into our consciousness. We got used to it. But there are consequences, which have been repressed and occulted from public, mainstream view for too long.

3. The consequences for Sharif: she has been denied childhood insofar as she has been made aware, from an early age, of how language boxes one in, as in “Expellee”:

Chest films taken at the clinic. The doctor’s softly

splintered popsicle stick. By five, I knew I was

a HEALTH THREAT. The daylong waits, the predawn lines.

Stale taste of toothpaste and skipped breakfast.

The No and Next metronome of INS. Numbered windows,

numbered tongues hanging out of red dispensers

you pull at the butcher shop. The ground meat left out

for strays, the sewing needles planted in it.

Health clinics, butcher shops. The red tongues, pulled out. Yet Sharif will not let her voice be taken away from her. There is too much to reckon with.

4. War has consequences, not only for Sharif but also for others in her life, dearly loved ones, like the uncle – her Amoo – whose death as a soldier in the Iran-Iraq war haunts the second half of the book: “You are what is referred to as / a “CASUALTY.” Unclear whether / from a CATALYTIC or FRONTAL ATTACK”.

Sharif’s parents fled Iran shortly after her birth, which means she was never able to meet her uncle; yet the process of recognition initiated through the poems, in spite of other people’s objections (“How can she write that? / She doesn’t know”) points to the necessity of the connection and of imagination, the latter being the only thing that can save us from the neutralizing effect of language. She imagines meeting her uncle, approaching him “in the new Imam Khomeini Airport” and saying she recognizes him, even though he “could be a number of brothers / from our albums”. Imagining him, giving him life beyond the photograph she has of him, is the only way to move beyond the mere acknowledgment of the cost of war. It is a means to to push back against the enduring narrative of erasure and oblivion.

5. Erotics and ballistics. That’s what it comes down to, really – the push and pull of eros and thanatos.

Let it matter what we call a thing.

Let it be the exquisite face for at least 16 seconds.

Let me LOOK at you.

Let me LOOK at you in a light that takes years to get here.

As citizens we were used to ignoring the parts where reality bursts at the seams with the force of unacknowledged violence. We were shielded, because neutralizing any empathy we might have for others, especially others outside of our borders, is the most effective way to ensure our unwitting cooperation in warfare. A condensation of searing vulnerability and potency, LOOK disrupts these habits, regains control of the narrative, forces us to look, again and again, at the world. After this, there is no longer any excuse to look away.