PASSING: BEYOND THE BODY

I'M NOT ALWAYS LOOKING TO BE REFLECTED BACK // a conversation with Jamal T. Lewis & Ashleigh Shackelford

// by L. G. Parker

Both Jamal and Ashleigh’s work consistently goes viral, making digital movements not unlike their own geographic movements from, to and throughout the American South. What does it mean for these two major cultural producers to be from the South even as the South is considered a space of lack and without production, unable to account for these identities considered to be new and cosmopolitan? Does it matter at all? Here we explore critique as a means of production, geography’s role in shaping their work and the limits of our collective “American” political imagination.

L. G. Parker: So both of y’all have lived/are living in the South. How has geography impacted the way(s) that your body has been read and how does that impact your work?

Jamal T. Lewis: (Laughing) Oooh.

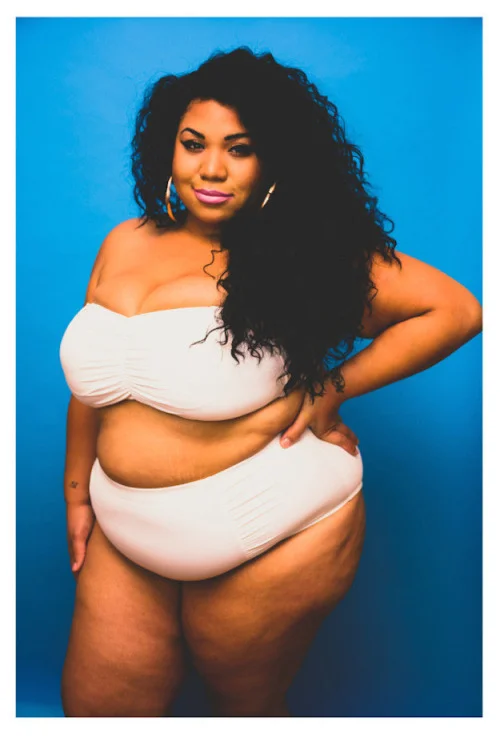

Ashleigh Shackelford

Ashleigh Shackelford: That’s deep (laughing) Oh, man. Wow. Well I would say that I feel like being in the South is so interesting being fat and black. I think it’s like there’s mad levels because for me personally, like especially experiencing what it’s like up in the North, I feel like I’m, I feel like my body is more… I think my body is more violated in the South in a different way. But I think that not just my own exploration of my body but how other people experience my body in their spaces, and I’ll call them “their spaces” because I don’t ever feel power in most spaces.

But I would say that, and my fatness has so much to do with my gender, because like in so many ways I feel like you don’t have to be non-binary to wrestle with gender. It wasn’t even until last year that I started identifying as non-binary but most of my experiences around being fat and black deal with being denied femininity and being denied womanhood, or even girlhood or innocence as a child living in the South. I've been fat my entire life, like I didn’t just turn fat a couple years ago, you know, I come out to the womb 11 pounds and then I was just big as shit my entire life so like I had always been experiencing people denying me gender, denying me safety, because of my fatness and blackness and I think geography and being fat in the South affected that because in so many ways like, I think there’s more mummification around my body in very specific ways because fatness in the south has such a deep history. It's a strange grappling with being sexualized while also being denied like sexual agency all at the same time. So it’s like you’re disgusting, you’re gross but your body is representing something else. I feel like in the North, depending on how I dress, people will be more voyeuristic like ‘oh my gosh, you’re giving me life’ and in the South it’s like a fat bitch is an everyday experience.

L.G.: I remember before you were talking about how your fatness forecloses people reading you as non-binary. Because of your fatness you’re just automatically read as femme, cis and binary.

A.S.: For fat people, if you’re not moving into masculinity, then your gender deviant identity doesn’t make any sense to them. I feel like femme is drag for me in so many ways because I was forced to be high femme as fuck to get any respect, or if I ever wanted to get a job you’re not going to catch me without a job. In so many ways, even if I wanted to be perceivably more “deviant” from what you would ascribe to my body as natural, I couldn’t even do that and survive and make any coin or presume anyone would love me or hold space for me. And I feel like because I’m not moving into masculinity and because I have to move into high femmeness, it’s so easy to literally ignore my actual gender identity -- not identifying as cis, not identifying as womanhood as an actual identity.

L.G.: What you’re saying, Ashleigh, about being denied girlhood and womanhood and now not being read as non-binary because of your body echoes what Jamal said in an LA Times interview about “failing gender.” You said, Jamal, that“People are afraid to wrestle with the fact that they too fail gender and are trans, in a way, and fail these normative notions of gender, particularly black people.” In conversation with that, how has geography impacted the way that your body has been read?

J.L.: One of the ways that geography has impacted the way my body is read is this notion that because southerns have wide hips, big buttocks, and warm hospitable spirits, that I am mutha — that I am here to produce [emotional] labor and inspiration for everyone that I come in contact with. That I can’t be sad. That I can only go through shit when it’s in the service on producing inspiration for other people on how I made it to the other side. It’s really interesting. And I don’t always have a problem with it, but it’s often dangerous when folks immediately typecast me as this thing denying me humanity, denying me complexity, and denying me a body to be defined and owned by me.

I think that’s interesting because it reminds me of how the South is never a part of our political imagination. It’s often assumed that nothing is occurring in the South when for years things have been happening in the South – very meaningful things – that don’t get the attention of, I guess, national media headlines or big media organizations because it’s not New York. I remember being asked in this Wussy Mag interview why I left the South, and when I thought about it more, I wasn’t really in a race for New York, it was really just about opportunity and getting away from my hometown. But even in just thinking about that question it just reminded me of these ideas of South/North, that one is incapable of holding space for gender deviance when they’re both equally tragic.

L.G.: Yeah, it just might show up a little bit differently. But what you said about us not seeing the South as a part of our political imagination – who is “our” when you say that?

J.L.: I say our as in… who is our… maybe, I guess, our as in liberal progressives, I don’t know what to insert.

L.G.: I thought you meant “our” as in everyone who is, as you said, gender deviant.

J.L.: No, no. I’m just thinking about liberal progressives. I just feel like the South is just always left out or just never imagined as a space deserving of politicization. Like it’s just always left out and it’s a place that’s always without resources

L.G.: And deliberately so.

J.L.: Yeah! And it’s just always imagined as a space without. And a space of lack.

Jamal T. Lewis & Ashleigh Shackelford

photo credit: NYU LGBT center

L.G.: Actually what you’re saying about it in the political imagination makes me think about, Ashleigh, thinks that you said in your Lemonade critique and how it was responded to. So you know how Beyoncé has all the mothers and then she has the scenes where there’s just random, everyday black women so you’re not looking at the famous light skinned black women, it’s just random dark skinned women, who show up in very quotidian scenes, then you have a few fat black women who are showing up in scenes of pain. So they show up to represent a lack that can be interpreted as, I guess, you know, having a sort of introspective value of inserting images of pain into something that is ultimately about overcoming that pain in a very triumphant, Beyoncé way. But they don’t really, on their own, hold a space of agency or participate in the braggadocio of the rest of the film. It’s just like… here’s an image of pain that should mean something to you in this context; let’s continue singing.

I saw a lot of anger in response to what you wrote about it, and I'm just thinking about how a lot of the responses were like, 'Oh well if you don't see yourself then produce your own images,' and it seems that what Jamal is doing with No Fats, No Femmes is easily legible as a production of images, while your critiques are read as a lack of production and just whining. What are your thoughts on critique as production?

J.L.: Right.

A.S.: I think that's such a great observation. When I saw Lemonade I was like, wow, you know, fat black women are being seen as accessory trauma tropes. And that's all we ever are. Our bodies only represent trauma. And that fucked me up. I feel like, you know, the response to anything that you critique -- and not just Beyoncé -- people are so ready to critique you for critiquing it. And I think that's an important place to be, too. Because I think we should challenge ourselves on why we critique but I think critique is a form of production, a form of creation and a form of art. How would we ever develop our political selves without questioning? Without saying, why do I have to be man or woman? What is right or wrong? What is this binary when your wrong doesn't look like my wrong? Are we going to gray that area? I feel like that is power. The work that Jamal does, the work that you do, L.G., and the work that I do is so important. We validate each other even if we're not doing the same types of work. That critical production and critiquing is very valid and important to any political movement, to all of our political selves, and I think that what fucks me up the most is that depending on who is doing the critiquing and how you're being viewed determines how valid people are willing to view your critique as. I think that being black and fat and just always being loud with my shit has always been an easy way to dismiss anything I'm saying. But niggas can't wait if I’m hyping them, you know?

J.L.: Right.

A.S.: But they can't take if my critique is not something that they're aligned with or makes them uncomfortable or is pushing them and in so many ways that also speaks volumes to the dehumanization of bodies like mine and Jamal's when we do anything that is not inspirational or is not happy. And when I say happy I mean that very politically in the sense that people always want fat femme sidekicks to literally be butterballs of joy or butterballs of shade for everybody else who's not you.

J.L.: Right.

A.S.: It reminds me of how often I'm disposed of through my critiques. Critiquing for me, before it was even political, even before I could name it as political, it was very personal for me. My mom who is also black who is also fat and femme, always taught me to say something if a space is uncomfortable because nobody is going to fight for you like you're going to fight for you. So I go into spaces now not ready to fight but ready to demand my humanity, ready to demand that spaces fit my body and ready to demand that space values/affirms me and doesn't try to take from or drain me. I feel like in so many ways having that presence also puts a target on me, people see me as just wanting to call stuff out. It has nothing to do with bitterness, but if I was bitter that's okay, too.

Anger and bitterness and any context of political ratchetry or being ratchet or ghetto are really confined to people we can still find beautiful and palatable. Being fat and black, [the reception of your work] depends on how people view you, if people want to hold space for you to have that range of emotions and a range of critique because people will ready to be like "bitch you're not cute enough to talk shit"

But apparently you have to be cute for people to hold space for you. So it's our form of creation and our form of humanizing ourselves and acknowledging violence when it happens to us. I critique to remind myself that violence is happening to me. When a room doesn't fit me, when seats don't fit me, but you invited me? You flew me out to come and talk but the room don't fit me and the seat has arms and you never once thought that damn this bitch has a disability and is fat as fuck like I have to let you know that this is violence.

And I don't say that to be like "everything's violence!" because I’m aware of how we cling onto words like violence and trigger and end up conflating everything as the same, but if a room is inaccessible, that is violence.

J.L.: People use that rhetoric -- or rather that mean internet meme logic, like, “be weary of people who critique but don't create." It's all a method of silencing people; folks who critique are people who other people just don't want to acknowledge as well as read. Don't get me wrong, I totally understand how critique can feel extremely harsh, shady, ill-mannered, or whatever other word you can think of to describe the feeling of being on the other side of things (I've been there); but I like to think of it as an invitation towards change and possibility, towards conversation, which, in and of itself, produces work that goes on, and on, and on.

L.G.: I think pop culture is seen as feminine and therefore dismissed as excess & so I see a lot of vitriol towards y’all questioning why you would spend your time critiquing pop culture as opposed to something else. Something else is always, you know, regarded as more important, more “real.” I think you've both started to discuss this but why do y'all choose to focus on pop culture as a site of analysis?

A.S.: Pop culture is not only something that everyone pays attention to, but media affects everything that we do. All I have to do is turn on my TV or go online to experience something where I’m engaging in celebrity culture or something going on in the world that affects me or people around me. How that media comes to me, how that media is relayed, how the story is framed and written, what images I see, all of these things are very political and affect everything that we do and affect how our identities are read. Media has the power to perpetuate propaganda around all of our identities and so in so many ways, challenging media and pop culture, which is all things that are popular that come to the forefront and things that people want to engage in, that also lets you know the climate that we're in.

J.L.: I failed what I saw reflected back at me in pop culture.

L.G.: You failed as in you didn’t look like what you saw and you couldn’t replicate it?

Jamal T. Lewis - photo credit: Giancarlo Valentine