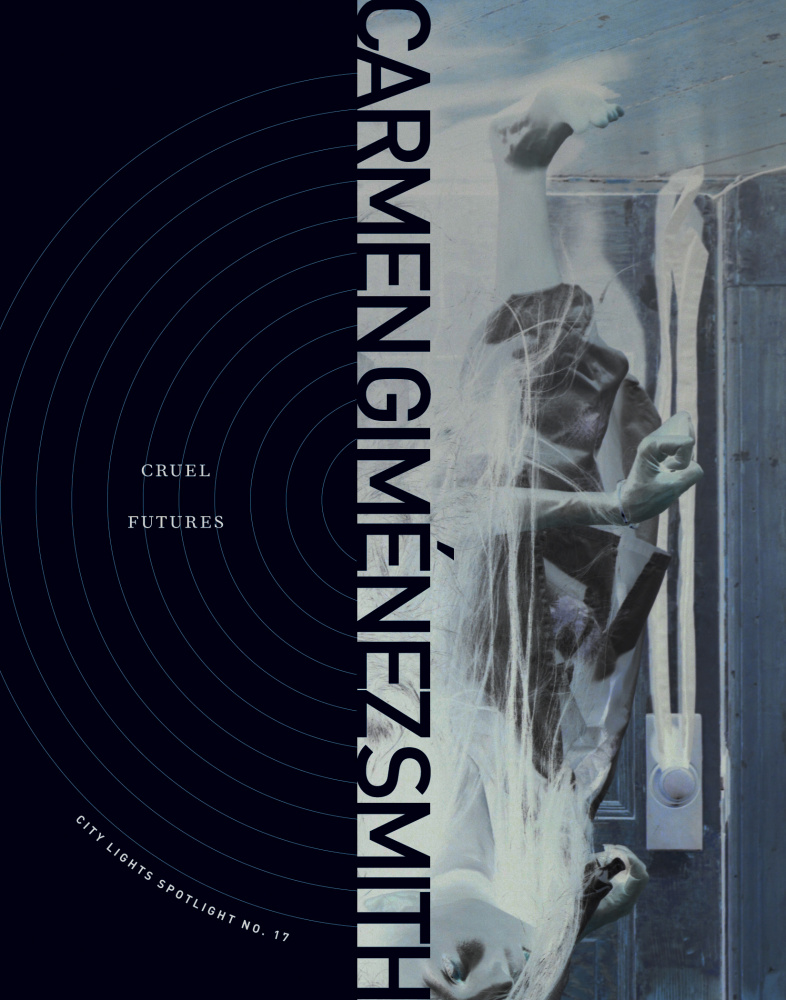

Cruel Futures,

Carmen Giménez Smith

// review by AK Afferez //

05.09.2018

In an interview last December with Cosmonauts, when asked what she would do if she won the lottery, Carmen Giménez Smith replied, “Buy a commune, pay off all my peeps’ debts, then move us all into the mountains as we inch towards the apocalypse.” Her upcoming collection, Cruel Futures, displays this same strong sense of community, and to be honest, I wouldn’t mind having these poems to accompany me through the apocalypse.

Cruel Futures is Giménez Smith’s fifth poetry collection, and the maturity of her work shines through every word. A prolific writer, in addition to writing a memoir, Giménez Smith has published poetry, both in full-length collections and in chapbooks, and has edited a short fiction anthology of stories based on fairy tales. Her capacity to weave together different narrative modes or voices is heightened in Cruel Features, especially since the collection, embedded in the speaker’s body as it is, seeks to bring to light the multiplicity of her experience as a middle-aged Latina woman and mother. In her position, she must contend with the myriad of ways society forcefully assigns her gendered roles and expectations. Smith doesn’t shy away from admitting that things like beauty are among her primary concerns; she doesn’t know what it is besides a “careworn tale” as the title puts it, a question that is relentless and provides no answer for women:

That was a recent revolution.

The moral of the story reads

On the day she truly realized

she was beautiful, she died.

But if there’s injunction, there’s also, always, an escape route. Here, escaping means embracing the inner monster, what lurks “on the corner of identity / and shadow” (“As Body”). To witches who ask “What are you”, the speaker answers, “a monster / of my own making.” That this assertion occurs in a poem named “Dispatch from Midlife” is no coincidence: middle-age signifies a repositioning, a radical shift in the perception of the self, since society ties up so much of women’s worth in youth. Later, the identification notably with Medusa, hailed as “one of the first witches” - a sorceress who gifted her story “to pre-feminism” - gestures at the creation of a lineage, one that will inspire to, in turn, shape the world in which she wants her daughter to live:

I am close

to setting my girl into the world, more she is

ready to launch into it. I want to clear the dross

of misogyny, so she won’t suffer under its yoke.

I’ll paint my face, take off my earrings, do the inevitable. (“Ethos”)

Monstrosity isn’t just about womanhood, but also about mental health. From the beginning, the weight of the medical lurks through the lines, as when the speaker writes:

Should have been born pale

scion or with less oddity, less

diagnosis.

Words like “narcissicism,” “mania,” or “anxiety” riddle the poems, and the speaker excavates them, trying to make sense of such clinicality, whether for herself or for others. In “Bipolar Objective Correlative,” the image of “a coil of lightning” helps the speaker understand the entanglements of the self, the mind, the body (“to erase / the self from the mind, if it / weren’t for the corporeal / muck”) that get her “twisted / into a monster.” In “Dementia Elegy,” the image of “sinister / motels,” haunted and abandoned, gestures at a deeper reflection on her relationship with her mother. Often, poems are a way to cut through the fog brought about as in “Migraine Code Switch,” where the back-and-forth between Spanish and English, the thrumming of alliterations, and the repetition of “títere” (“puppet”) are all strategies to name and write through the sensation so as to regain some sense, some form of control over one’s body and mind, similar to the isolation chamber Giménez Smith later describes in “Oakland Float,” a chamber which allowed her to “know what [she] was without the noise of the world / buzzing in [her].”

In Cruel Futures the poems perform a special kind of sleight-of-hand, misdirecting your attention so you are expecting one thing, and thus preparing you for the full force of the punch a few lines later. Take the opening poem, “Love Actually” - it’s funny, it’s about pop culture and mumblecore, it’s short and ironic, but also wistful. Turn the page, and “As Body” has you spiraling into a sharp-toothed reflection on growing up as a girl, as a “trouble magnet” whose body “unhinges at the psyche.” The speaker never minces her words: “I grew up on the edge / of your electrified fence / like a weed.” In turn, the portrayal of her relationship, later in life, to motherhood and to her children shows that tenderness and sharpness of insight are far from incompatible: in “Ravers Have Babies,” she explores the kind of lineage she is transmitting to her children. Her tone is often humorous, as she explains that “I didn’t make them organic or French yet / I think it’s too late but we’ll live”; but the final lines of that poem offer a sudden pang of poignancy: “To them the imaginary is still marvel / though each minute inverts them away from me”. Motherhood, like womanhood, is nothing stable; it requires a constant reshuffling of perception.

This is a collection of incredible humor, wry and witty. In the opening poem, she mentions things that don’t exist, “like / unicorns and democracy”; later she skewers the mainstream complacency with Nazism, gentrification, white supremacy and current governmental “Voldemort style management.” “Use Your Words,” an abecedarian mismashing contemporary political buzzwords, reveals the extent of linguistic distortion in such a political climate. Smith tackles existential crises and pop culture in the same breath; she confronts the ways TV has shaped her relationship to the world and to reality through a series of mordant observations on race, gender, and violence in media. She riffs off Adam Smith’s assertion that “All money is a matter of belief,” casually asserting: “I’d sell my soul, but there aren’t any takers.” And if Cruel Futures ends on a lullaby, it is meant as a song to jolt you awake.

A.K. Afferez is the Director of Spotlight Series at Winter Tangerine. Recent poems have appeared in Teen Vogue and Wyvern Lit; in parallel, they write for the Ploughshares blog and serve as Nonfiction Editor at Vagabond City. Favorite small talk topics are lesbian history, tarot, and the apocalypse.