My grandmother, his wife, has a more subtle way of sharing stories. She didn’t command a room like my grandfather, all six feet and some change with booming voice; no, she stayed in a room quietly with her barely five foot frame and voice that strained with effort to be heard over our family. Whereas my grandad was more active volcano, my grandma was the reminder of rupture, the bubbling underneath the surface that you feel when you walk, something you don’t notice until it’s lost forever.

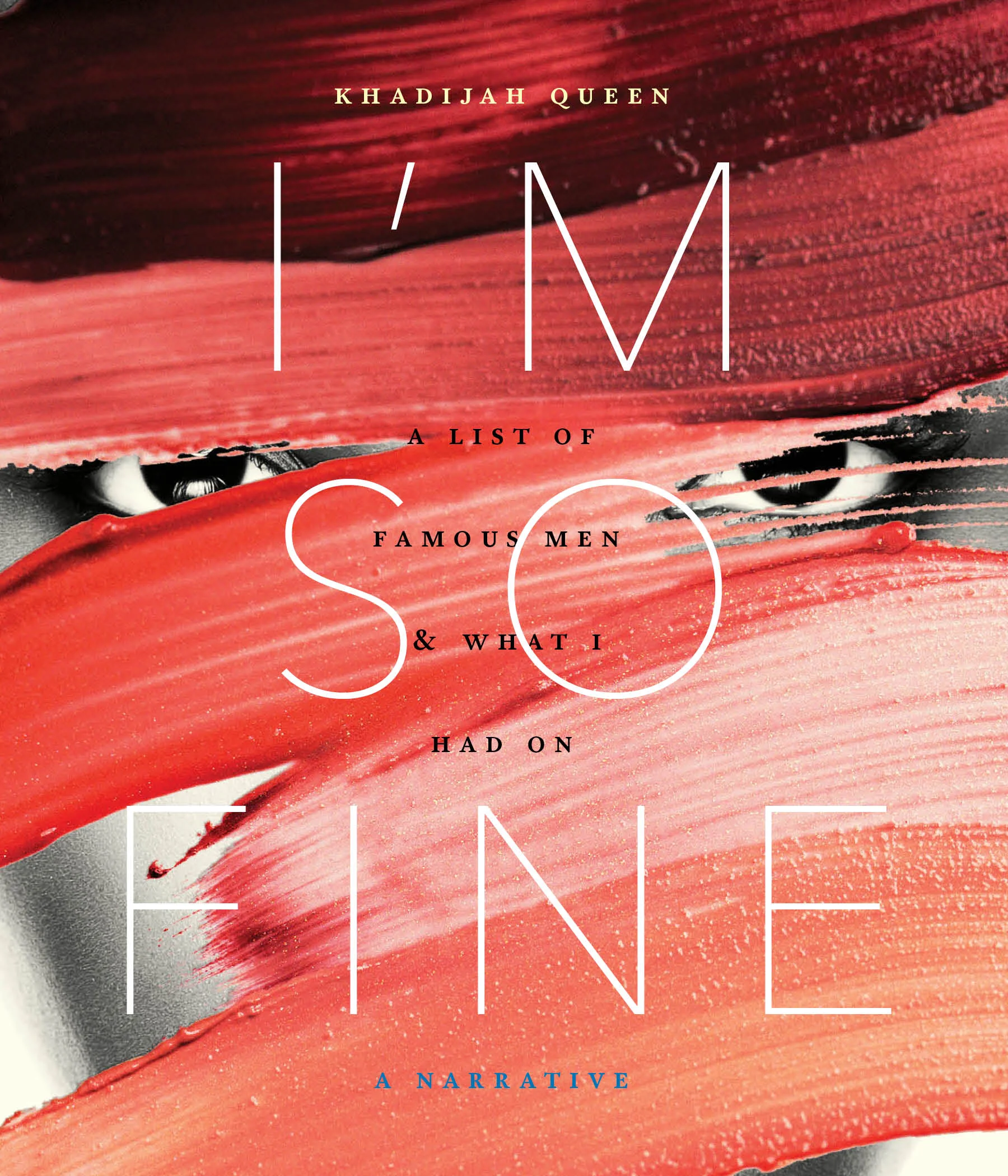

I had never imagined what it might look like to hear my grandparents tell a story in unison until I read Khadijah Queen’s fifth book, I’m So Fine: A List of Famous Men & What I Had On, published by YesYes Books. Queen is also the author of Fearful Beloved (Argos Books, 2015), Black Peculiar (Noemi Press, 2011), and Conduit (Black Goat, 2008). In I’m So Fine…, Queen slides from story to “oh shit!” real quick and back again.

A master of subtlety, Queen tells (seemingly) simple stories that interest the reader at first, but gnaw at you as you turn over the underneaths of the story later. Because even though you feel like you’ve learned so much about her, there are still pockets where you’re not sure you know the whole story, or even understand it. There are still places where if she kept telling the same story, you’d still find yourself surprised, looking at her in a new light, thinking, “How could I have missed that?”

In her encounter with Suge Knight (through a friend), it took me three times to read to notice the weight of “& I won’t say if my coworker got hurt but she made a fact out of fear”. I was so busy thinking about Tupac’s passing and the clothes her friend wanted her to upgrade to (Girbaud and Gucci and Chanel) that bruises and bloodied anything were far from my mind. Queen captures truth through ordinary so well that the violence flew right over my head. On the third read, I had just seen Michel’le’s Lifetime movie, Surviving Compton: Dre, Suge, & Michel’le and as soon as Suge’s name came up, the red flag popped up with it. My eye caught that line this time and hung over “& I remember makeup over bruises the 1990s dangerous for women like any other decade like now” and this poem wasn’t just about Suge and his girlfriend but also about my aunts and my friends and the deep scooped out feeling when you can’t fix a love that can’t be love in the first place. I never would’ve noticed it if Queen hadn’t told me to look for it.

This is a book that can be read through one sitting but it doesn’t mean it’ll be finished with you once you close the book. I carried it around with me for two weeks straight because I didn’t want to be finished with this experience. I thought the famous people would be the stars of Queen’s book, but I could care less about Morris Chestnut and Danny Glover (which is saying something). By the third or fourth poem, I didn’t care very much about these dudes, aside from the landscape they created. Before I was even a quarter of a way through the book, I just wanted to hear every story Queen wants to share. The men she uses are good at grounding the reader. Queen knows you may get lost so she’s generous enough to give the reader something to hold on to. The outfits point towards where we should look when Queen speaks and the men gesture to your seats, but that’s all they serve as: ushers to the main stage. The men make your heart flutter a bit but Queen is so damn real and powerful that she outshines them all. Which isn’t surprising as she writes: “[...] I am tough enough to know what I can take & satisfied with keeping stars on the screen & out of my eyes my well-used heart”.

Through this book, Queen gives a lesson that all black women need: you (and by extension, your story) are important, crucial, and absolutely necessary. Black women need to chronicle their lives, to keep it permanent, especially when the world really just doesn’t give a fuck about them. Queen doesn’t write about a life lived, she writes about herself still living. In her second to last poem she writes: “[...]& when I was young I could in equal measure celebrate & take everything about living for granted but 40 is so cool 40 is seeing & knowing not seeing & wanting 40 holds beauty as the accumulation of bliss & survival”. Queen’s strength lies in not just giving the past its space, but tying it to her present, her past’s future, giving us a chance to know her as a full person, not just snapshots.

This book is telling the same stories again and again anytime your family comes together, but this time you pick up on important intricacies that you were too young to notice before. The types of poems Queen shares are the magic of someone letting you in--but only as far as they want you, and you being grateful for anything they give you. This collection of poems is learning to hold that delicate right. Reading A List of Famous Men..., you don’t realize Queen hasn’t said her own name until the postscript. In the last poem of the book, “Any Other Name”(the first and last poem with punctuation), Queen writes:

“[...] My mother told me I should keep some things to myself. She should have said keep yourself to yourself but it was in her nature to be generous.

I learned that kind of giving leads to further taking and it’s a light that attracts parasites.”

Though Queen reminds black women that we should tell our stories, we aren’t required to give everyone everything. There isn’t shame in keeping the heart of yourself, for only yourself.