Barrett reminds me, gently and resolutely, that, for real, “Homebois Don't Write Enough.” The poem is a celebration of becoming through boi-ness - what we are now, and most importantly, what we can be. It is a call to action for those that fumble with masculinity, a call to leave space for tenderness, to welcome a capacity for softness.

homebois, we don't write enough love poems to ourselves.

spell out our soft syllables unapologetically, letting

our strength beyond stiff jaw and cold silence,

the stuff of abandoned buildings.

I can remember clearly the way the room hummed when Barrett delivered his poem, "make us a legacy that is beyond all this,” his voice carried earnest and fiery, creaking with the urgent exhortation.

In my living room there are pictures from when I was young enough to be posed in the gauzy, uncomfortable dresses standard issue for Latinx daughters. One portrait shows a toddler me in satin pink dress, with white lace about my neck and wrists. There is an era of pictures like this; I know it broke my mother's heart that dresses and gold jewelry were never right for me. Sometimes the pictures are so disorienting to look at, and when I sit with Barrett, I feel him acknowledging just how much work my girlhood has done to build a new masculinity for me. Barrett writes “let us unfold the photos with us dipped in lace and dresses and / laugh and maybe even keep it, rejoice!” and I marvel: what a gift it is to be an adored daughter with puffy braids, what a gift to be the black boi I am today, what a gift to be of ancestors and mothers.

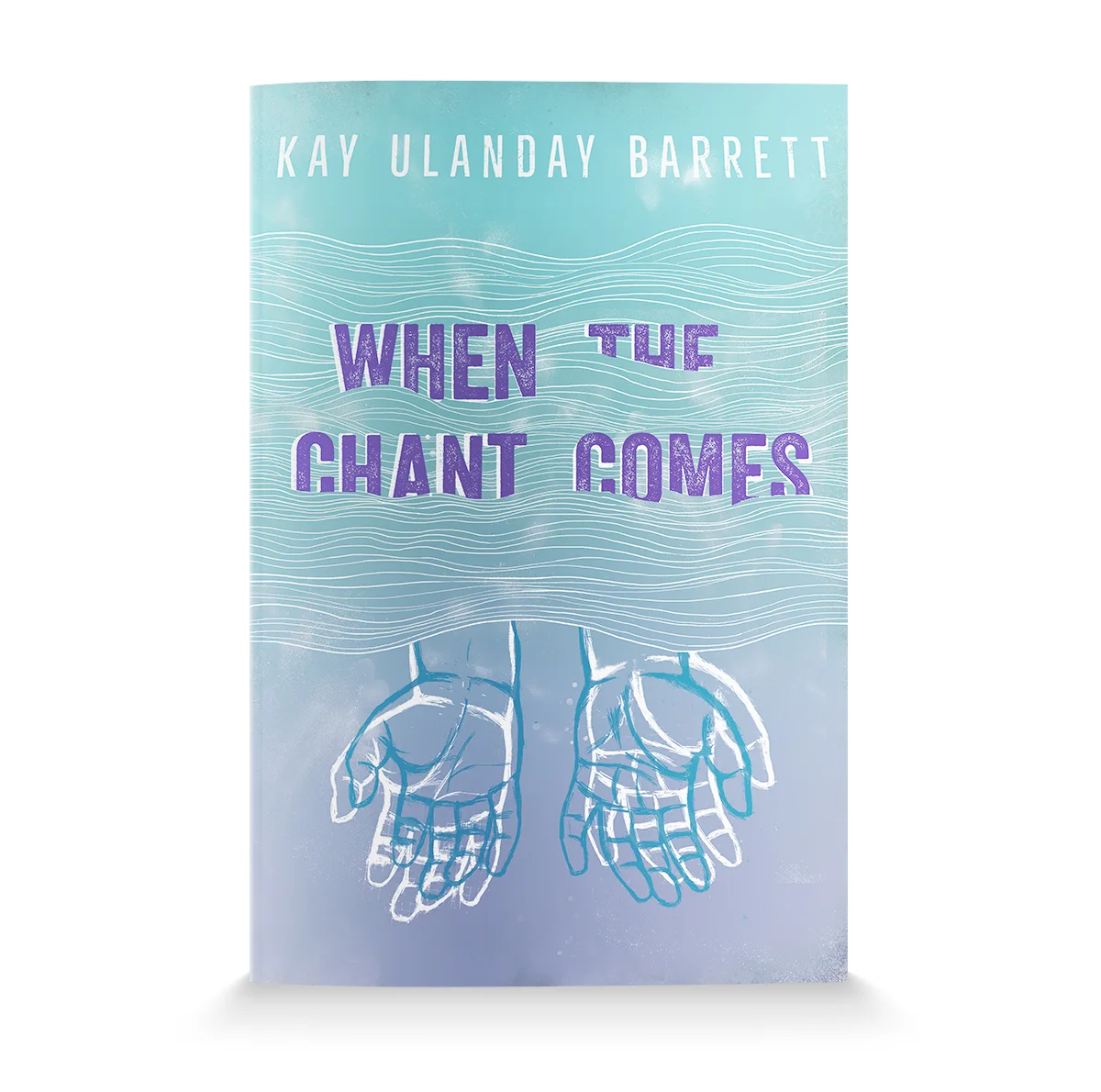

Kay Ulanday Barrett’s When The Chant Comes is presented in five sections, titled in Tagalog and english. They are: “katarungan: justice,” “mahal: love,” “karamdaman: sickness,” “kamatayan: death,” “kapwa: soul.” The book is curated and intentional, demonstrating the breadth of Barrett’s writing skill. In works such as “Somewhere A French Braid Is Intimidated” and “Never The Forest” poetry pushes into prose, mirroring the composition of a lyrical essay. Barrett has a skill for rendering the vitality of spoken language onto the page, flexed in the way the very text of “Rhythm is A Dancer” reverberates in the ear, as if heard in real time.

Working with a local queer youth theatre company this past year, it made an innate sense for me to incorporate Barrett’s poetry into my agenda. As a guest teaching artist, my role was to help spark conversation around the meaning of words like ‘home’ and ‘safe/safer/brave space’. I would offer up examples of how across media, queer artists explore the idea of ‘home,’ a central theme to the production the students of the company were working to co-create.

I shared “Rhythm Is A Dancer” with the group and it was an honor to be present in the triumph of lines such as, “We come from ancestors who drum and dance, / who made sweat rivulets alongside the tears / because movement had to start first on the body.” Over the course of our three rehearsals, I began to grow concerned that our students would quickly get over When the Chant Comes, simply because of how much I talked up the book. It just made sense, It was hard not to share the ways in which this small book had helped me carve out a corner of the world. In one workshop, we went around the table reading poems stanza by stanza. As I had hoped, giggles arrived when we reached the line about “big gay pyrotechnics,” and I knew, instantly, that we were vibing.

“Rhythm Is A Dancer” contains so many wry quips about the glorious messiness of growing up young and queer. Even though none of us in that room had hung out in Chicago’s Logan Square, Barrett’s poem brought to mind Copley fountain and the BAGLY dances each of us had attended. There was a heavy, indulgent sigh that hung in the space when we reached the lines, “We kissed hard. / We held hands.” My heart ached with how full it was, and all I could do was to thank everything that had allowed me the capacity and the honor to be present in such a moment with these young artists.

While reading When The Chant Comes, a word that stays on my mind is 'longing.' Barrett renders in language the physical pull of desire. In the poem “Uncertain” Barrett writes, "The weight this body / holds includes my mother's voice, her clock / runs by overtime shifts and the current warring of her / birthplace can't enter her mind, / she doesn't have the time.” Through snippets, a story is told, carried by the timeline-defying power of immigration, the power of being a culmination of ancestors across time and place. Barrett captures definitive moments that detail the experience of being of a diasporic, immigrant family; there is the snapshot of egg rolls, dominoes and coca cola on a table and the muscle memory of unintentionally acquired skills: "You can text message fast from years of phone card dialing / in panic. Because your lola / fell once again. Because money" (if your family is forced here).

Another word that stays with me is ‘monument.’ When The Chant Comes is a monument to the love act of writing, a building of a universe through rendering small moments mundane and significant. Barrett builds a monument to all that has combined to make this work of poetry. Ancestors and chosen family are brought along in the very poems, memorialized and shouted out, celebrated and lifted up. When I praise Barrett, I am also praising people who have influenced him in his life, for they are present and proud, people who I will never know but have benefited from encountering.

When I closed When The Chant Comes, having read every poem once through, I could only be grateful. This book brought me into all my feelings, whether I wanted to be there or not. My gratitude goes to the strong voice that kept me company as we sat present in trauma, joy, need, connection, loneliness and glory. You should buy this book and take it in. Order two because, I assure you, someone needs it.